Blog

Since the clocks went back in October, streets and public spaces have been plunged into darkness from as early as 4pm, meaning that many people find themselves doing every day activities such as commuting and exercising in the dark.

We recently undertook research to understand the differences in public perceptions of open spaces at different times of the day. It found that four out of five people feel more unsafe when it’s dark and are on average 12 times more likely to avoid certain areas than in daylight hours.

How safe do people feel in public spaces?

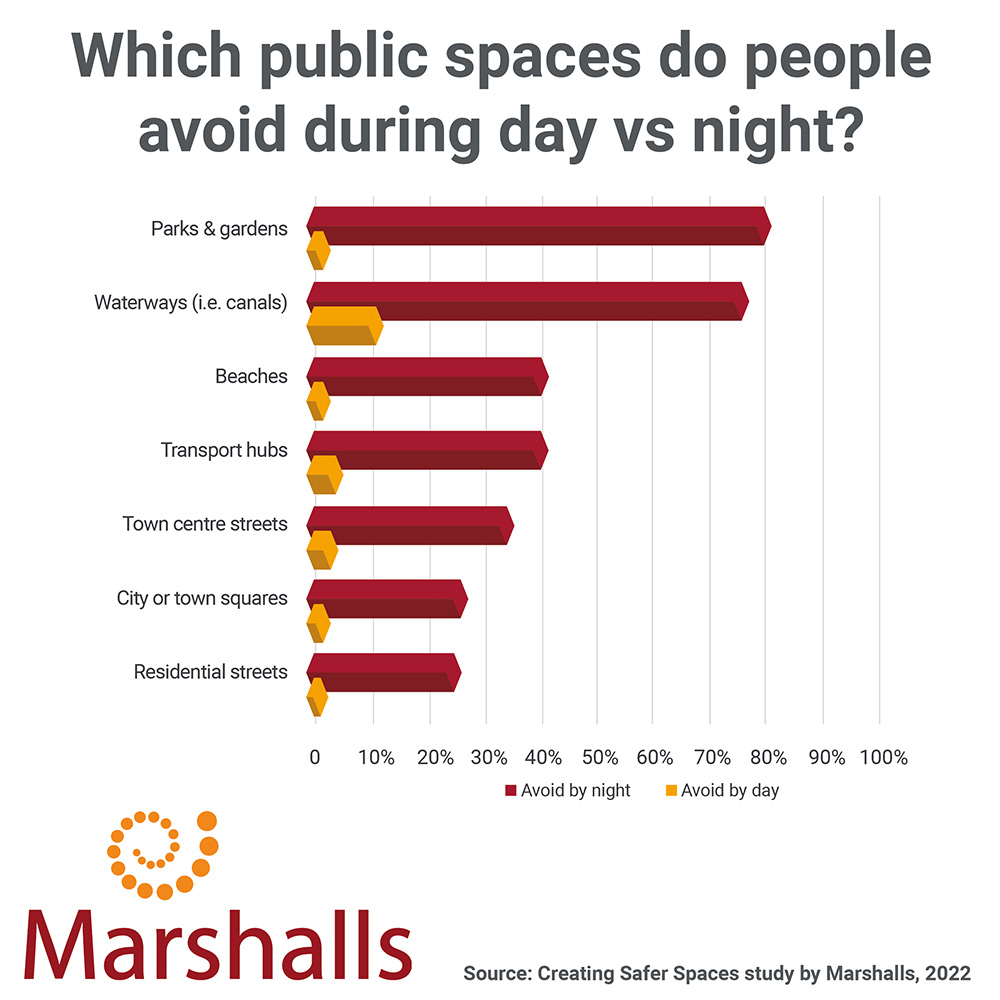

As part of our Creating Safer Spaces whitepaper, we found that parks and gardens were considered the least safe spaces when it’s dark, with 80% of people avoiding them during this time – a huge 40 times higher than in the daytime.

While 11% of respondents said they avoid waterways, such as canals, when it’s light, this figure increased almost seven times to 76%, when its dark. Residential streets were considered the safest of all public spaces, yet nearly a quarter (24%) said they still avoided them when it’s dark. Beaches, transport hubs and town centres were also named as places people would avoid primarily when it’s dark.

Off the back of the findings, we’re urging the industry to consider how to approach designing for the dark, so people feel – and are – as safe accessing spaces in the dark as when it’s light.

To achieve this, we’ve outlined a set of key design principles for architects, designers and planners, focused on wayfinding, lighting, acoustics and more, which – if put to use – would improve perceptions, and use, of public spaces during darker hours.

Why do people feel unsafe in public spaces?

To ensure we crafted design principles that would have a positive effect on the public, we explored the reasons why people have a heightened awareness of safety when it’s dark and the actions they take when they feel unsafe.

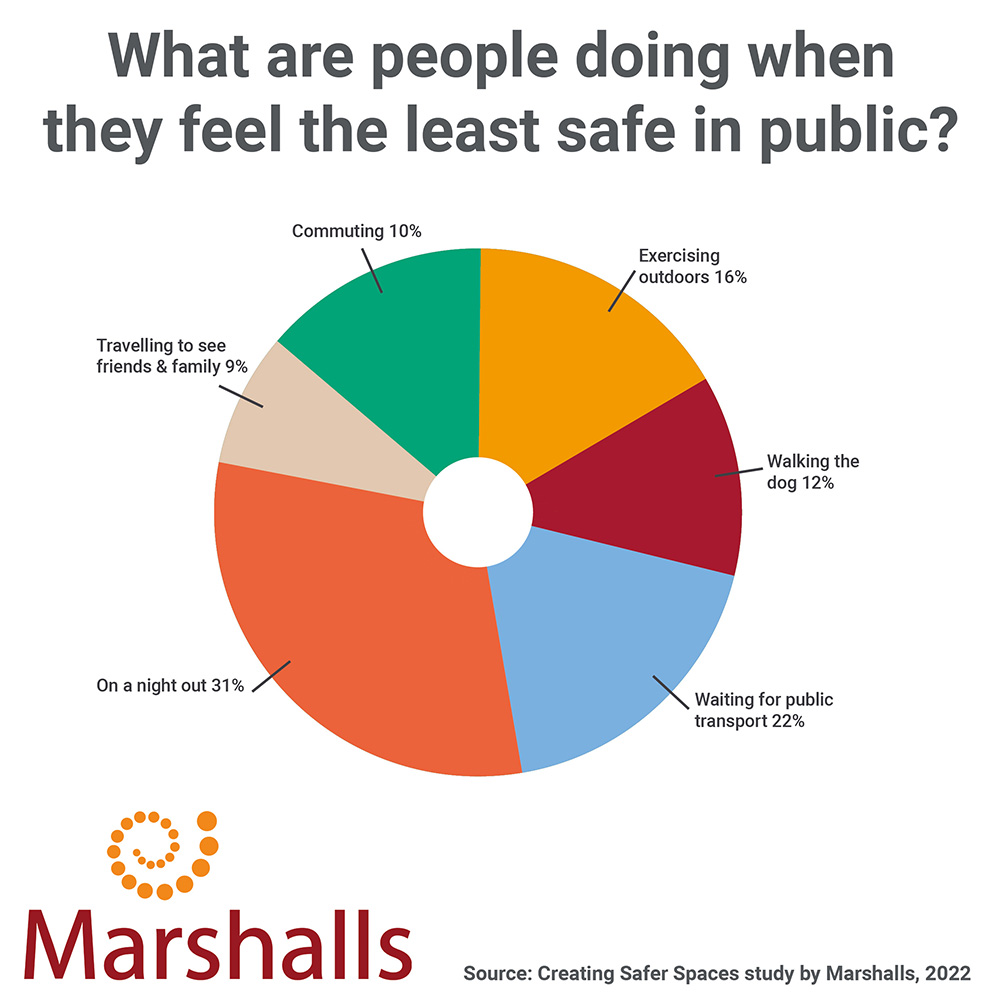

Our research revealed that people feel most at risk on a night out (31%), with waiting for public transport (22%), exercising outdoors (16%), walking the dog (12%) and commuting (10%) also creating feelings of a lack of safety.

Respondents cited poor visibility as a key issue, whereby potential dangers or hazards are concealed or out of sight. A lack of ‘social presence’ from reduced use of spaces by people when it’s dark was also raised as a reason for safety concern.

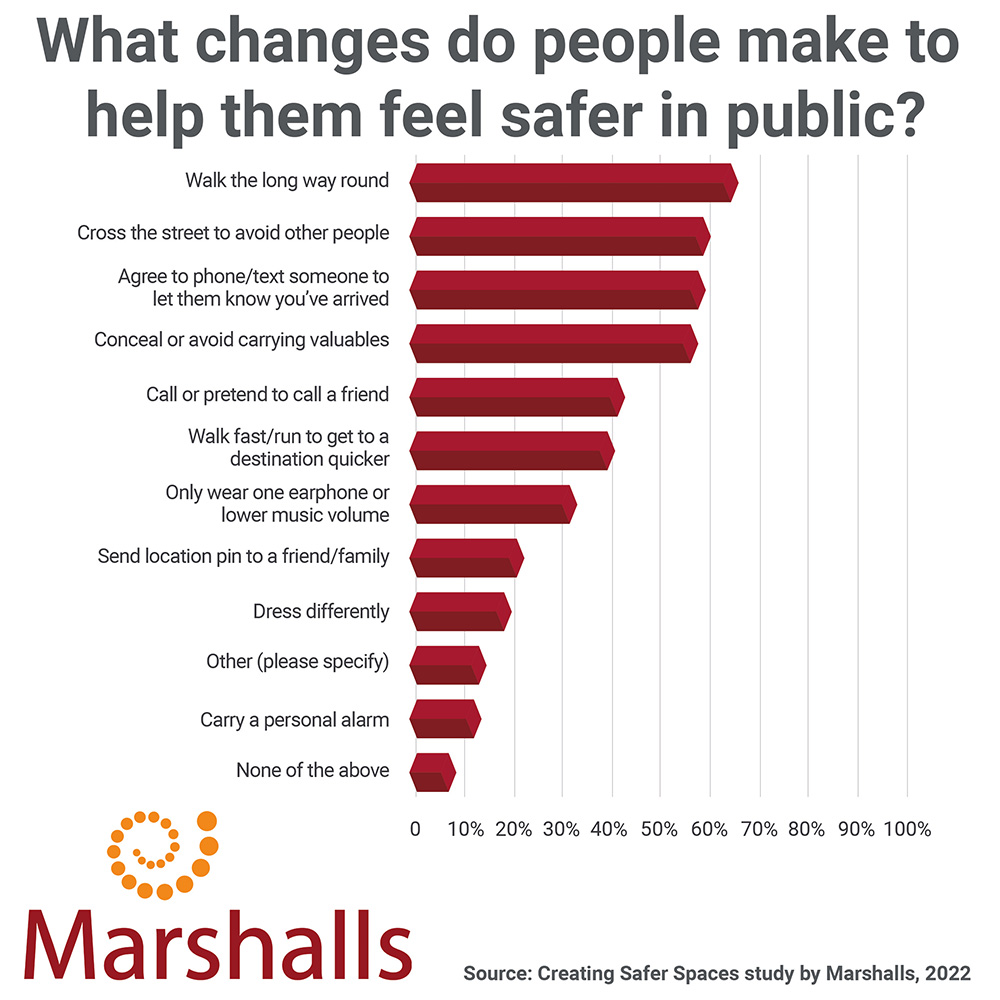

The results also showed that people commonly change their behaviour to improve their perceived levels of safety when out in public. The most frequent modification was walking a longer route that is busier and/or better lit (64%), followed by crossing the street to avoid others (58%). Further changes included only wearing one earphone or listening at a lower volume (32%) and carrying a personal alarm (11%).

How can we better design public spaces for the dark?

To help the industry create safer spaces from day through to night, and to provoke fresh thinking and debate on how to approach designing for the dark, we’ve outlined seven best practice design pillars:

- Eyes on the street

- Vision and wayfinding

- Acoustics

- Accessibility

- Familiarity

- Technology

- Maintenance

These pillars are discussed in great detail, referencing studies and including examples, in the Creating Safer Spaces whitepaper (keep reading for the download link). All these things should be considered during feasibility and concept stages of any public realm design as they can be seamlessly integrated, and even enhance other key principles – such as biodiversity and accessibility – with compelling results.

Creating safer spaces by using the design pillars

There are different ways each of these pillars can be considered when it comes to designing for the dark. For example, wayfinding and acoustics for night time hours can often be overlooked when new schemes are in the planning phase. However, simple design choices such as the height of a hedge or the use of materials that better absorb echoes and rogue sounds can have a big impact on the perceptions of safety and therefore how much people use them throughout the day, and year.

In our research, good security technology in the form of CCTV cameras and other deterrents – like dynamic lighting – was considered very important by almost 60% of participants. With this in mind, security experts should be engaged in the early design stages of a public space so that safety is ‘designed in’. For example, our research showed that more than half of people will call or text a friend or family member on their journey home as the remote presence of a familiar person improves their feeling of safety. To support people who feel the need to take this action, offering free public Wi-Fi, boosting local networks or providing ‘StreetHubs’ like those seen from BT should be a matter of course in developing public realm spaces.

Finally, many of the survey respondents said that familiarity makes a difference to their overall feeling of security when interacting with a space, so using recognisable design features should be a priority. For example, using locally sourced building materials in areas of regional heritage helps people to develop more of a connection with a place. Plus, where feature repetition is successfully integrated into the urban realm, users no longer need to be concerned with what ‘lies around the corner’ as a certain level of comfortable predictability takes effect.

Making spaces feel safe in the dark won’t be achieved by thinking tactically; it requires a strategic approach that results in creating open, accessible spaces where people feel seen. It is also multifaceted, required to create a lasting change in behaviour and understanding across the industry, and all of society.

Our priority is helping the industry to make spaces beautiful and welcoming, thus attracting more users, and fostering a sense of civic pride. This requires a holistic, innovative approach to how people plan and create spaces. Our research shows there’s no better time to begin working towards that, because the potential results could change the way we all live, work and interact forever.

Read the full Creating Safer Spaces whitepaper