Why does block paving fail? Uncovering the misconceptions

Small element paving, or as we know them today - blocks, setts or paviours is not a new phenomenon; the principle of using small individual units as a surfacing material can be traced back to ancient times. So, one of the answers to the immortal question “What did the Romans ever do for us?” is actually paving!

Roman Road, Blackstone Edge, Rishworth Moor, Lancashire

Today, we see hundreds, if not thousands, of block paving stones every day. They feature prominently on UK high streets, retail parks, leisure destinations and commercial spaces, among other high-traffic areas. Yet, some common misconceptions remain about how block paving systems work and why they sometimes fail.

In this guide, I explore the reasons why one of the UK’s most widely used paving solutions can end up failing or needing to be replaced prematurely. Using 30 years of hands-on experience working on my fair share of paving installations (the good and the bad), I’ll share insights on how you can ensure your next project is equipped to meet the needs of its users and built to withstand the test of time.

(Note: The guidance in this article is based on unbound (flexible) paving constructions where the paving units are bedded and jointed with sand as opposed to bound (rigid) constructions).

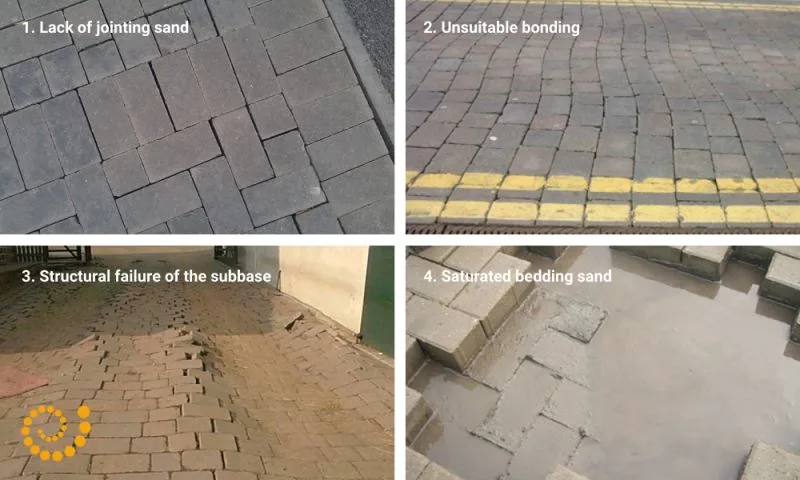

Above are examples of why block paving fails, find about more about each image in more detail below.

- Lack of jointing sand

The addition of block paving sand (also known as jointing sand) between the paving units is not simply for aesthetic appearance or to fill in the gaps. In an unbound construction, the joint is an integral part of the structural performance and should be viewed in this way.

When loads are applied to the surface, it is the frictional interlock between the side of the paving unit and the sand joint which prevents the paver being depressed and transfers the load sideways into the next unit and joint. This basic principle allows small element block paving to work as a collective surface and support incredibly heavy loads.

If jointing sand is lost due to poor placement and compaction during installation or, more commonly, a lack of maintenance or aggressive cleaning, individual blocks begin to move and lose their ability to disperse the load.

Left untreated, the issue snowballs with blocks moving laterally and more sand being lost, eventually unravelling the entire surface. Sand loss is perhaps the single most common cause of failure in unbound paved surfaces and can be avoided with good joint filling and vibration during installation and an appropriate maintenance and cleaning regime during service life.

You can read more about unbound paving pros and cons here.

- Incorrect bonding

The laying pattern of block pavers is more than just an aesthetic feature; it’s a crucial structural bond that can make or (literally) break the integrity of the paved surface.

Selecting the right bond pattern for a given application is as important as any other aspect of the structural design and should never be made solely on the basis of visual appeal.

Several bond pattens can be considered, each with its pros and cons, with the most common being herringbone, stretcher bond, random coursed and stack bond. Selection of the right bond pattern is related to the level of interlock that can be created - the stronger the interlock, the greater the surface ability to resist movement. That movement typically comes from vehicles turning, breaking and manoeuvring.

The orientation of the bond pattern to the direction of vehicle movements should also be considered, particularly with linear bond patterns such as stretcher and random coursed which have little or no interlock between individual courses.

If we were to rank the four bond patterns mentioned above, herringbone would be the strongest, followed by stretcher bond, random coursed, and finally stack bond.

Although the herringbone might not be viewed as the most aesthetically exciting bond pattern it provides the strongest interlock and will always be the bond of choice for frequent or heavy vehicle movements.

Stretcher and random courses have some structural interlock but are typically only suitable for very light traffic or pedestrian applications. Stack bond has no interlock between the courses in either direction and should only be considered for pedestrian use.

- Subbase failure – what lies beneath?

Paving manufacturers will be familiar with the claim of “your paving is failing”, only to arrive at the site to see an area of deep settlement or depression in the surface and sublayers. In reality, it is very rare for a small element paving unit to fail itself, i.e. slit or break in half.

Structural failure or settlement of the paved surface is most often linked to issues within the underlying structural layers and these failures are being reflected at the surface. The causes of structural failure can vary and require further investigation and inspection to determine the issue. Key areas to consider would include:

- How you arrive at the original structural design

- What parameters were factored into the design (traffic loading, ground conditions etc.)

- How was it installed and if it adhered to the structural design

- What level of trafficking the surface receives and whether this matches the design parameters

A major settlement should always be dealt with by uplifting areas of the surface course and visually inspecting the sub layer materials. It should not be rectified by simply relaying the paving units to level as this only masks the issue in the short term and can lead to further issues.

Good structural design and specification, high build standards on site, and appropriate use of the completed surface are key to a successful project.

- Saturated bedding layers – nobody likes a soggy bottom!

Unbound paved surfaces are generally considered to allow a degree of surface water to pass through the sand joints and into the underlying layers. If moisture can pass through the construction freely, no major saturation concern exists.

Saturation of bedding sand can occur when non-porous materials such as tarmac or insitu concrete are introduced as structural layers within the construction. Any moisture penetrating the upper layers can become trapped within the bedding sand as it cannot percolate any further into the construction.

If the paving is subjected to regular heaving vehicle loading then the saturated sand is compressed and forced up through the joints to the surface. This causes displacement of the bedding sand, leading to movement and settlement within the paving. A tell-tale sign is often the presence of displaced bedding sand on the surface and the paving units sitting in a puddle of water above the non-porous material.

To overcome this issue, drain holes can be core drilled through the impervious layer at 500mm spacings and filled with a free-draining granular material. Each hole should be covered with a geotextile material to allow moisture to pass through but prevent loss of jointing sand.

Over time, the sand joints do naturally seal themselves with dirt and detritus and will reduce the amount of moisture passing through, but this cannot be solely relied upon, particularly during the early life of the paving.

- Incorrect paving choice

With a vast choice of paving types available, selecting the right plan size can be a challenge, and as with other design considerations noted here, this should not be led purely by aesthetics.

The structural design of the paved surface will ultimately drive the selection of the appropriate plan size and thickness of paving, and of course, further expertise is available from the manufacturer. That said, there are some basic principles to follow.

The larger the plan size, the less suitable the paving unit is to deal with heavier vehicle use, unless the thickness also increases considerably, which may not be practical. Hence, larger paving flags are more suited to lighter use and pedestrian applications and smaller, deeper block paving is suited to heavier or frequent vehicle use.

The guiding principle with paving selection is always to consider the worst-case loading, even if that is only very occasional. Other options include blending different surfacing types using block paving in the frequently overrun areas and flag paving where vehicles cannot physically reach.

If you’re wondering whether unbound paving is the right solution to specify for your project, learn more by reading about the pros and cons of unbound modular paving or contact the Marshalls team for information tailored to your application.

The Marshalls Design Team consists of designers and pavement engineers that have seen it all and supported on countless projects across the UK to avoid instances such as these, all while saving customers cost, time and carbon in their projects. If you require support on your next project get in touch here.